Uganda Stands #WithRefugees

On 4 June this year, I made my first ever visit to Uganda, baptized as the 'Pearl of Africa' by Winston Churchill. Returning to East Africa always brings good and bad memories that I have learned to accept and cherish. I come from this region of Africa which is the cradle of humankind. Although wars made me face challenges at a very young age, I remain attached to the people and places that played a role in shaping the path I am on today. And that is the pleasant feeling. My birthplace South Sudan has recently made positive strides on the political front, and we continue to pray for long-term stability. The efforts to bring peace will only be meaningful when the millions of my people now living in asylum in Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan and Uganda, or huddling in internal displacement sites in South Sudan will feel confident that it is safe for them to return home. Since I was appointed as a UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador a year ago, I have become aware of the devastating consequences of conflict. Mind boggling statistics (65.3 million people displaced worldwide; 18.4 million in Africa) represent children, women and men experiencing suffering through violence, forced displacement, death, disease and global inequalities that impact humanity negatively. And of course not to mention lost opportunities.

Little Keysha from Burundi snuggled next to me as we watched refugee youth from Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo perform traditional dances and theatrical dramas at a refugee community centre in Kampala. Children below 18 years of age constitute about half of the refugee population in the world, requiring focused efforts to address their needs and minimize the impact of forced displacement upon them. [UNHCR/Teresa Ongaro]

These are the issues I reflected upon as I prepared to travel to Uganda at the beginning of June. I had been told the experience would be transformational. It was hard for me to imagine how I conditions for refugees could be different from what I have always known. I expected to find overcrowded encampments, with refugees living in clusters of makeshift structures in remote and under-served parts of the country, as I have seen elsewhere in the region—where, despite the best efforts of governments, the United Nations and NGOs, any human dignity is daily eroded by total dependence on aid and bleak self-reliance prospects because of lack of opportunities. I do not wish to undervalue the work and contributions of the international community, but to offer the perspectives of the millions who, through no fault of their own, are punished by having to spend decades of their lives in refugee camps; where their future is gloomiest. The average period that refugees spend in asylum is 17 years. It is a harsh reality for anyone whose only crime was to be born a citizen of a country that is involved in war. For many individuals, the asylum period stretches to 30 or even 50 years.

In Rwamwanja Refugee Settlement, several refugees families who had arrived in Uganda in from the Democratic Republic of Congo a few days previously, were in this holding area waiting to be allocated the plot of land that will be their new home in Rwamwanja Refugee Settlement. [UNHCR/Teresa Ongaro]

Visiting refugee camps as an adult I realize that I was too young to appreciate the indignity of that experience when I first became a refugee in Itang, western Ethiopia aged nine or ten. My mother, my younger siblings and I had arrived in Itang frail and in distress from traveling for nearly two years from village to village looking for safety, food, shelter and news of lost relatives. People from all over what was then called Southern Sudan were fleeing war in the same manner. We were hunted down by an enemy that I knew simply as “The Arabs”. Antonov and ground attacks burned entire villages and terrorized unarmed villagers. We walked for weeks and months, sometimes, splashing -- during the rainy season when the Nile overflows -- in water that rose above my chest, the tall grass of the jungle providing cover from attacks. We learned to ignore the hunger pangs. Mostly we fed on unripe mangoes and water lilies, thankful to be in survival mode. I remember how adults screamed at the older children to run ahead. People dragged the injured and the young, and elderly. Some survived the bullets only to be eaten by wild animals or succumb to disease, hunger and exhaustion. Others drowned in the rivers, like my little twin sister Nyandit. By the time we arrived in Itang, we were accustomed to running for dear life to escape attack. I tried hard to forget those days. Although death and disease were commonplace, Itang was like heaven compared to the Sudan we had left behind.

Under the hot afternoon sun, I got to plant trees at Nyamiganda Primary School in Kyangwali Refugee Settlement. The school was started by a (South) Sudanese refugee who since returned home. I planted paw paw, jack fruit and guava trees, here with shy little Zawadi, who is from D.R.Congo. [UNHCR/Teresa Ongaro]

Later, in the early 90s, I became a political refugee again in Walda and Ifo camps, two of the five camps that make up the Dadaab complex. The landscape is desert-like; the climate unpleasantly harsh. Dadaab then was a toxic melting pot of traumatized refugees including youth and adolescents like myself; survivors of the brutal wars that then raged in Ethiopia, Rwanda, Somalia, Congo and my own country, then Sudan. We had violent confrontations, attacking each other and exchanging blows, cracking our skulls with bricks and clubs, fighting in the only way that we knew how to resolve differences and I was always in a thick of it. Although I was older, I looked beyond the difficulties and indignities of being a refugee in Dadaab. Like others, I was consumed with a burning need to go abroad to find school and work to support my mother and my younger siblings. I had left them eking out a living in our conflict-ridden homeland. In Dadaab we all prayed and waited patiently for news that we had been selected to go abroad. All we wanted was the chance to see a better day ahead. My prayers were answered and I was resettled to America, eventually. I contemplated those experiences as I prepared to travel to Uganda. I wished I had something more tangible than words—messages of hope—to bring to the people I would meet.

Kevin and his friends kept me company at COBURWAS Primary School, a community led and founded school in Kyangwali Refugee Settlement. [UNHCR/Teresa Ongaro]

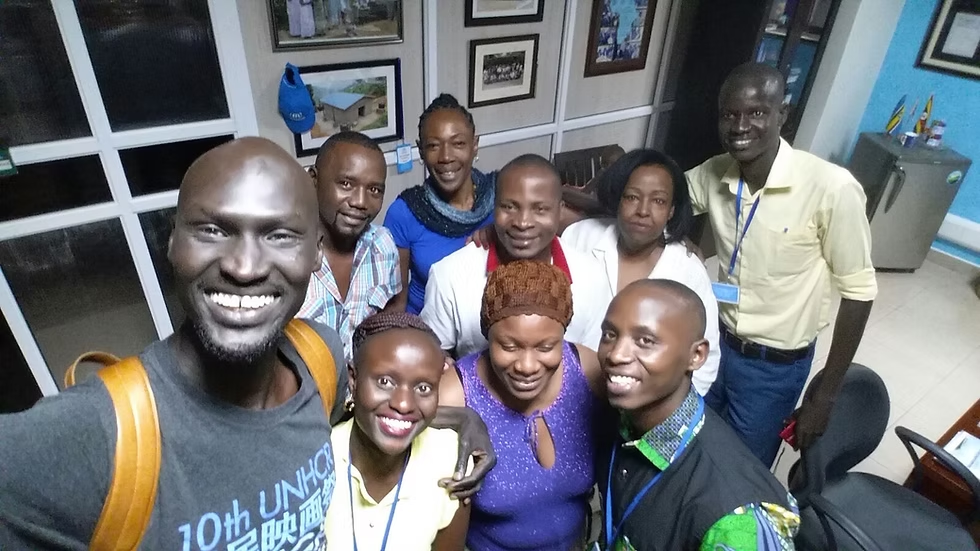

Instead, I was pleasantly surprised and deeply impressed. Uganda has more than half a million refugees and asylum-seekers. It is the third largest refugee-hosting country in Africa and the eighth largest in the world. There are no refugee camps in Uganda. The Government has gazetted land for refugees to settle while in asylum. Where refugee-hosting districts do not have gazetted land, the Government negotiates with leaders from the host community to allocate area for refugee settlement. In some areas, refugees make up more than one-third of the total population. The settlement approach allows refugees to live with dignity, independence, and to work closely with Uganda nationals. The refugee settlements are administered by the Government, who register and provide documentation to the population, allocate land for shelter and subsistence farming/agriculture, and provide security. Refugees in Uganda enjoy freedom of movement. With their identity cards, they can live anywhere in the country, and seek education as well as employment without discrimination. Those who choose to live in urban areas must be economically self-reliant. They do benefit from the same social services that are provided to Ugandan nationals. In the coming days I will share stories about youth that I met in Uganda and the amazing things I saw. Please follow my blog. Uganda stands with refugees. I stand #WithRefugees. UNHCR stands #WithRefugees. Please stand with us. www.withrefugees.org(link is external) Ger Duany